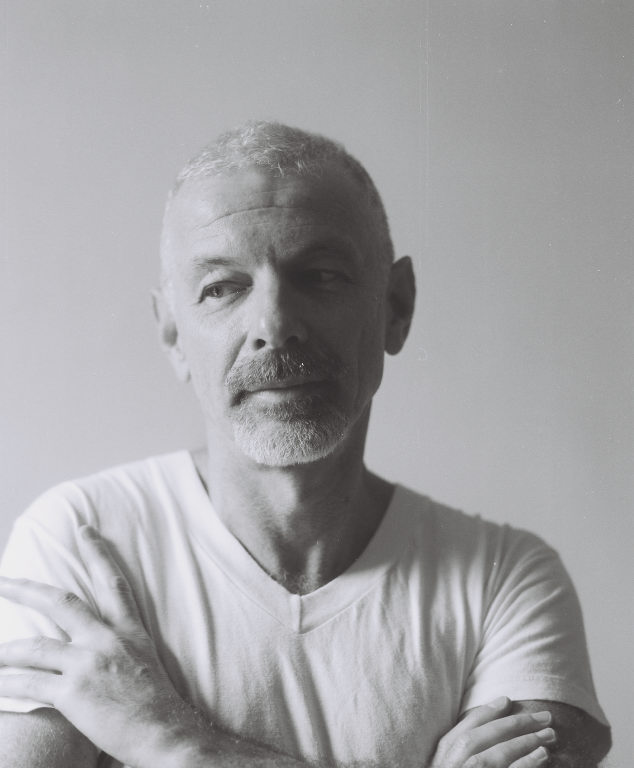

Perry Brass 1971 | image: J. LaRue

I met Perry Brass in October of 2007. He thanked me for a review I wrote about J. Louis Campbell’s biography of activist Jack Nichols. Campbell ended the book with a memorial poem Brass had written for Nichols: “…your life took on doubt and pushed it away like a faulty raft,” went the farewell. Brass is a genre-defying writer whose work has been included in 25 anthologies, and he continues to mentor with his words; 50 of his poems have been set to music.

Chris Delatorre: 1969, 2009. What’s changed? What hasn’t?

Perry Brass: Everything has changed, and too much hasn’t changed. I grew up in the Deep South, in the late 50s and early 60s, in a world where you could not even use the word “homosexuality” in any public form of conversation or writing. I had a college dictionary that did not have it in it: it was considered too obscene for college students. I came out at 16, and was really out (sneaking into gay bars) at 17. And I had nowhere to learn anything about who I was or what I was. My biggest feeling was that being gay I’d be murdered. I heard kids in the South talk about the properness of killing people like me all the time, while they weren’t even aware one of those very same “queers” was in the room.

All that has changed. There is now a lot of information about people who lead non-straight lives, whether they are gay, lesbian, bi, trans, or a combination of them. None of this has come about accidentally, through passive osmotic social changes, etc. It’s come about basically because of activism, and actively confronting prejudices and stupidity — although the cataclysm of AIDS certainly sped things along. It became impossible to hide when your friends were dying. And maybe you were as well. So AIDS was the Gay Holocaust, and like the Holocaust, it has activated people in ways that were impossible to predict. One of the things I love about this period of time, besides the amazing candor about the body, its joys and illnesses, is that people, especially young people, can imagine huge changes. Without this imagining of change, ideas like gay marriage and true gay equality could never have surfaced and actually flowered.

I was in GLF from 1969 to 1972. During that period, the same sense of imagining change was also working big time. In the Gay Liberation Front, we dared to imagine change in ways, on scales, that most of the world at that time never dared to do. We could dare to do it, and in very radical ways. It was a wonderful time to be alive and to be working for change.

On the other hand, that sense of imagining change is still barely working in a lot of people, especially LGBT people who are still frightened of coming out, letting people see that being different does not mean the end of life, and who are frightened because of ingrained violence in their own communities. So I’d love that to change. I’ve said that I would know we have really experienced change when someone like Derek Jeter can come out. And when I can see gay couples walking down the street holding hands in any American city and being treated casually, but with respect. When gay people don’t have to feel that constant sense of being self-conscious, having to hold back their own sense of tenderness and closeness because of defensiveness, when we can feel as unselfconscious as anyone else. I would love to see that. And of course I’d love to see us smile a lot more at each other. I remember that first Gay Pride Parade, which was actually called the Christopher Street Liberation Day March, in June of 1970, when we all smiled at each other, and we were hugging and kissing when we got to the Sheep’s Meadow in Central Park, and I felt that I now had about 5,000 friends, because that was about as many as there were there, and all of them, for that moment, were my brothers and sisters.

Steve Grossman (L), Ron Hellman, Miles Brown, Perry Brass | image: Dave Healey

Delatorre: How would you compare the GLF, back in the day, to the modern gay rights movement? How have we moved forward? And are there ways in which we’ve collectively moved backward? How much of the GLF’s original vision, would you say, has survived?

Brass: I think that the gay movement has evolved somewhat evolutionarily: it has adapted to the times, which is a good thing in some ways and a terrible, ugly thing in other ways. One thing that most people don’t take into consideration, and that we, as gay liberationists from GLF understood from the get-go, is that almost dyed-in-the-wool prevalence of internalized homophobia, that insidious repugnance queer men, especially, feel toward each other. No other minority group has it to the degree we have, and for good reason. As Harry Hay said, “Because our parents rejected us, we reject each other.” Therefore, we now see a gay movement (and I don’t say “gay liberation movement,” because I feel that gay liberation pretty much died about 1974) infected with celebrity worship, that denies the real importance of LGBT leaders who come out of the movement (in other words, we must be recognized by the straights before we’ll recognize each other), that is totally money oriented, that goes from crisis to crisis with very little history or foundation behind it. GLF had none of that. We wanted to create an authentic gay culture, a real gay media, and a gay world that was part of the bigger world and yet distinct enough from the mainstream for us to survive intact in it.

What has survived from GLF? An understanding that gays are a natural part of human existence; that we can heroically work with each other (GLF proved that, before GLF this idea was ridiculed. As Mart Crowley said in The Boys in the Band, “Show me a happy homosexual and I’ll show you a gay corpse.”); that there is a real foundation to homophobia that is not predicated on our being sick, sinners, or whatever: homophobia is a useful tool of a society that crushes people for being different; that patriarchy and its main product, sexism, can be seen, defined, and understood — so we can work against sexism.

Mart Crowley | image: Stathis Orphanos

What did not come out of GLF? An understanding of what is the male role in society and life, and how that role can be enriched, be made more wonderful to participate in. Also, GLF had a poor understanding of transgenderism. That would come later.

Delatorre: How were you involved with the GLF publication Come Out!

Brass: I joined GLF because of the paper, truly. I had been writing gay material before, and had finished a gay novel when I was 19 years old. I was told there was no way in hell I could get it published. Which was probably the truth. So when I heard about GLF and the paper, there was this instant attraction to me. I joined the paper in its 3rd issue, and published poetry in it under the name Mark Shield, although my name appears on the masthead. By the 4th and 5th issues, I was writing regularly for it. At the end of the 5th issue, the paper had to find new leadership and a new “office.” Our office had been a bedroom in an apartment in the East Village. So I agreed to publish the paper out of my Hell’s Kitchen walk-up apartment, and became, basically, the leading force on the paper, keeping it together and both guiding it and taking a lot of heat, since the paper was always extremely controversial. We published the next 3 issues from my apartment.

Here is a brief excerpt from a talk I’ve given about Come Out! It says a lot about the paper and my involvement with it:

My first intention on joining GLF was to work with Come Out! the first paper with a political mission of gay liberation in the world. I officially joined the paper in its third issue. It was then being produced out of Lois Hart and Suzanne Bevier’s loft on 6th Avenue near 38th Street, across the hallway from Sue Nagrin’s Times Change Press, another “movement” publisher. The guiding light of the paper at the point was Lois, who is now deceased. Although the paper was conceived as a collective, Lois was purely its leader, and Lois definitely had a point of view from that period of that first wave of lesbian feminism. I got along fairly well with her, and she used to refer to me as her “favorite male chauvinist.” To Lois, all men were male chauvinists, and all men oppressed all women.

Lois came from a Catholic background, and this became the guiding catechism of the collective. It did in fact, alienate her from the street queens, or the STAR girls whom Lois thought aped women without being them, and some women found Lois to be rather heavy handed and bridled against her. But she had a huge passion for the paper and she used every resource she had to get it out. She and Suzanne had a house painting business, and we used their van to pick up the bound copies of the freshly printed paper from the Movement printers who often printed Come Out! on the sly, after their regular jobs at commercial printers were done.

One of my favorite stories was the whole collective coming out in the van to pick the paper up at 1 o’ clock in the morning after it had been run on very clickety off-set presses in Brooklyn by a team of hippy printers who to make “bread,” or money, ran advertising circulars during the day. We had to jump over fences to get into the back of the print shop, and finally, by 3 AM the paper was piled up in the back of Lois’s VW van. On the way back to Lois’s loft, where we would bring the bales of Come Out! up 4 flights of stairs, Lois announced that all of the printers had been tripping on LSD while they printed Come Out! Aw, those were the days!

Delatorre: You participated in Gay May Day in 1971, the protest in Washington, D.C., and shared a brief account in Come Out!

Brass: It would be hard to describe those events in a short paragraph, but what May Day in 1971 showed was a willingness of a huge, mass movement, the Peace Movement of the 60s and early 70s to embrace LGBT people as co-participants and allies. Contrast that with the Democrats (forget the Republicans), religious organizations, etc. The Women’s Movement had already embraced lesbianism by this time, which led the way for the Peace Movement to do so. How this event differed from today was the personal connection everyone felt to everyone else. People instantly talked to each other, felt close to each other, linked with each other. There was not that constant digital alienation we have now, with everyone locked into his/her own little Blackberry screen, texting their brains out.

Perry Brass, NYC 2008 | image: Noa Baak

Delatorre: How do you feel about marriage for same-sex couples? Any reaction to President Obama’s recent take on the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA)? Would you say that the gay community is galvanized behind this issue?

Brass: I am totally for the rights of marriage for same-sex couples and am delighted that this issue has taken off so fast, because married couples get perks in America that single people can’t approach. In my GLF youth, the idea was ridiculous: we wanted to do away with marriage, monogamy, bridal registries, and the whole edifice and industry of marriage and married life. We wanted communal housing, communal marriages, communal child care, etc. There is some vestigial enthusiasm for this still, but on a personal human basis, communal marriage and communal childcare is extremely difficult and requires a lot of discipline. How this would be arranged can be severe, so we get right back to a one-on-one marriage ritual. Obama is still woefully inadequate about LGBT situations. I think a lot of it is ignorance: he hasn’t been educated about them, but I really think he is open to being, as compared to the Republicans before him. He is very much a political person, but not in the vein of Bush, Jr., and the Republican thugs who took over the White House for 8 years.

I think that the community is very much behind gay marriage, but unfortunately the reason is that gay marriage is very palatable to many Americans: it is so perfectly aligned with American consumerism and corporatism. Numbers of corporations are hugely behind gay marriage, and why shouldn’t they be? You get two now for the price of one: two extremely hard-working people joined to work for a necessary salary by the obligations of marriage. GLF wanted to do away with those obligations so that you could have a life that would create real world change. Who can change the world when they’re working 10 hours a day for MicroSoft or Disney, have a mortgage to pay off, are raising kids, and have no nourishing outside connections except their own couplehood? That is the American suburban dream, and queers have bought beautifully into it.

Perry Brass | image: Jack Slomovits

Delatorre: What comes to mind when I say “separate but equal”?

Brass: Of course what was going on in the South of my youth. In my lifetime I have gone from segregated drinking fountains at the Sears & Roebucks in Savannah, Georgia, to a black president. So, of course we may come to the same turn of events in the gay and lesbian struggle, although there are big differences.

Delatorre: Looking back on your life, is there anything you wanted to do but didn’t? Any regrets?

Brass: It’s very hard for me to have regrets because I believe that to change things you have to change the cards you were dealt in the first place, and my hand had a lot of difficult cards in it. But I would have wanted to learn more from the people who were there to teach me — all kinds of people, some of whom my GLF brothers and sisters really looked down upon as not being P.C. enough at the time. And I would have tried to carry Come Out! much further than I did, but at that point in my life I had very little organizing, promotion or personal skills. My greatest skill was just being able to survive. It’s extremely difficult though to go back; you have to understand that what we did in GLF was really earth-shaking, and that is the only word for it. Most of it was about 15 years ahead of its time, at the least.

Delatorre: Who or what would you say, in 2009, is your greatest enemy in the fight for equality? Your greatest ally?

Brass: The greatest enemy is always passivity and inertia. It is no longer coming from the Christian Right, although they are always there, just waiting for their turn again, and they will get it. Our greatest allies are young people all over the world who will not be murdered anymore, not be put down and put back, who want to be a part of their own liberation, who have come to realize their own value. I am grateful to have been a part of this struggle, and grateful for all the men and women who sacrificed so much. I have loved all of them.